to what extent was germany to blame for the outbreak of the first world war 1? tangled alliance

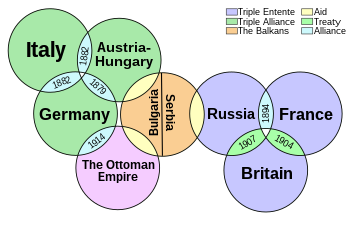

Military alignments in 1914. When the war started Italian republic declared neutrality; in 1915 it switched and joined the Triple Entente (i.east. the Allies).

Federal republic of germany entered into World War I on August ane, 1914, when information technology alleged state of war on Russia. In accord with its state of war plan, it ignored Russia and moved first against France–declaring war on August 3 and sending its chief armies through Belgium to capture Paris from the north. The German invasion of Belgium acquired Britain to declare war on Germany on August 4. Most of the primary parties were now at war. In Oct 1914, Turkey joined the war on Federal republic of germany's side, condign role of the Central Powers. Italian republic, which was allied with Federal republic of germany and Austro-hungarian empire before World State of war I, was neutral in 1914 before switching to the Centrolineal side in May 1915.

Historians take vigorously debated Germany's role. One line of estimation, promoted by German historian Fritz Fischer in the 1960s, argues that Germany had long desired to dominate Europe politically and economically, and seized the opportunity that unexpectedly opened in July 1914, making Germany guilty of starting the state of war. At the opposite cease of the moral spectrum, many historians have argued that the war was inadvertent, caused by a series of complex accidents that overburdened the long-continuing alliance system with its lock-step mobilization system that no–i could control. A third approach, especially important in recent years, is that Deutschland saw itself surrounded by increasingly powerful enemies–Russia, France and Britain–who would eventually vanquish it unless Frg acted defensively with a preemptive strike.[1]

Background [edit]

As the war started, Germany stood behind its ally Austro-hungarian empire in a confrontation with Serbia, just Serbia was under the protection of Russia, which was allied to France. Germany was the leader of the Key Powers, which included Republic of austria-Republic of hungary at the start of the war too as the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria; arrayed confronting them were the Allies, consisting chiefly of Russian federation, French republic, and Britain at the beginning of the war, Italia, which joined the Allies in 1915, and the United States, which joined the Allies in 1917.

In that location were several main causes of World War I, which broke out unexpectedly in June–August 1914, including the conflicts and hostility of the previous four decades. Militarism, alliances, imperialism, and ethnic nationalism played major roles. Still the immediate origins of the war lay in the decisions taken by statesmen and generals during the July Crisis of 1914, which was sparked by the bump-off of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of Austria-hungary, by a Serbian secret organisation, the Black Mitt.[2]

Since the 1870s or 1880s all the major powers had been preparing for a large-scale war, although none expected one. Britain focused on edifice up its Royal Navy, already stronger than the next ii navies combined. Germany, France, Austria, Italy and Russia and some smaller countries set up conscription systems whereby young men would serve from one to 3 years in the army, then spend the next xx years or so in the reserves with annual summertime preparation. Men of higher social status became officers.[3]

Each country devised a mobilisation organisation whereby the reserves could be called up quickly and sent to key points by rails. Every year the plans were updated and increased in complexity. Each country stockpiled arms and supplies for an regular army that ran into the millions. Germany in 1874 had a regular professional army of 420,000, with an additional 1.three million reserves. By 1897, the regular German language army was 545,000 strong and the reserves 3.four million. The French in 1897 had 3.four one thousand thousand reservists, Austria 2.6 one thousand thousand, and Russia 4.0 million. All major countries had a full general staff which designed war plans against possible enemies.[four] All plans chosen for a decisive opening and a short state of war.[v] Deutschland's Schlieffen Plan was the almost elaborate; the German Army was then confident that information technology would succeed that they made no alternative plans. Information technology was kept hugger-mugger from Austria, as well as from the German Navy, the chancellor and the foreign ministry, so in that location was no coordination–and in the cease the program failed.[vi] Indeed there was no joint planning with Vienna before the war started—and very piddling afterward.[7] [8]

Leadership [edit]

Historians focus on a handful of German leaders, every bit is the case for most countries in 1914.[9] For Deutschland special attending focuses on the Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg, thanks to the discovery of the very rich, candid diary of his top adjutant Kurt Riezler.[10]

Wilhelm 2, High german Emperor, the Kaiser, was given enormous publicity past both sides, and signed off on major decisions, but he was largely shunted aside or persuaded past others.[eleven]

Helmuth von Moltke, the Main of the German General Staff, was in accuse of all planning and operations for the German army. He kept his plans quiet. He had the Kaiser's approval, only did not share any details with the Navy, the Chancellor, or his allies. Increasingly every bit a crisis grew, Moltke became the near powerful man in Federal republic of germany.[12]

Public opinion [edit]

Public opinion and force per unit area groups played a major part in influencing German politics. The Army and Navy each had their nationwide network of supporters, with a million members in the German Navy League, founded in 1898,[thirteen] and xx,000 in the German language Regular army League, founded in 1912.[fourteen] The near articulate and aggressive civilian organization was the "Pan-German language League".[15] The agrestal involvement was led by large landowners who were especially interested in exports and was politically well organized. Major corporations in the steel and coal industries were constructive lobbyists. All of these economical groups promoted an aggressive foreign-policy. Bankers and financiers were not as pacifistic every bit their counterparts in London, but they did non play a large role in shaping foreign policy.

Pacifism had its ain well-organized groups, and the labour unions strongly denounced war before information technology was declared. In the 1912 elections, the Socialists (Social Democratic Party or SPD), based in the labour unions, won 35% of the national vote. Bourgeois elites exaggerated the implicit threats fabricated past radical Socialists such as August Bebel and became alarmed. Some looked to a strange war as a solution to Federal republic of germany's internal problems; others considered ways to suppress the Socialists.[16] SPD policy limited antimilitarism to aggressive wars—Germans saw 1914 as a defensive war. On 25 July 1914, the SPD leadership appealed to its membership to demonstrate for peace and big numbers turned out in orderly demonstrations. The SPD was not revolutionary and many members were nationalistic. When the war began, some conservatives wanted to apply forcefulness to suppress the SPD, but Bethmann-Hollweg wisely refused. The SPD members of parliament voted 96–xiv on three Baronial to support the war. At that place remained an antiwar element especially in Berlin. They were expelled from the SPD in 1916 and formed the Independent Social Democratic Party of Deutschland.[17]

Newspaper editorials indicated that the nationalist right-fly was openly in favor of state of war, fifty-fifty a preventive one, while moderate editors would just support a defensive war. Both the conservative press and the liberal press increasingly used the rhetoric of High german award and pop sacrifice, and often depicted the horrors of Russian despotism in terms of Asiatic atrocity.[18] [19]

German language goals [edit]

Historian Fritz Fischer unleashed an intense worldwide debate in the 1960s on Germany's long-term goals. American historian Paul Schroeder agrees with the critics that Fischer exaggerated and misinterpreted many points. Notwithstanding, Schroeder endorses Fischer's basic conclusion:

- From 1890 on, Germany did pursue world power. This bid arose from deep roots within Frg's economic, political, and social structures. One time the war broke out, world power became Germany's essential goal.[xx]

However, Schroeder argues, all that was non the main cause of the state of war in 1914—Indeed the search for a single main cause is not a helpful approach to history. Instead, at that place are multiple causes any one or two of which could have launched the state of war. He argues, "The fact that so many plausible explanations for the outbreak of the war accept been advanced over the years indicates on the one mitt that it was massively overdetermined, and on the other that no attempt to analyze the causal factors involved can e'er fully succeed."[21]

Historians have stressed that insecurity almost the hereafter securely troubled German policy makers and motivated them toward preemptive state of war before it was too tardily. The nation was surrounded by enemies who were getting stronger; the bid to rival British naval supremacy had failed. Berlin was deeply suspicious of a supposed conspiracy of its enemies: that twelvemonth-by-yr in the early on 20th century information technology was systematically encircled by enemies. At that place was a growing fear that the supposed enemy coalition of Russia, France and United kingdom was getting stronger militarily every year, especially Russian federation. The longer Berlin waited the less likely it would prevail in a state of war.[22] According to American historian Gordon A. Craig, it was after the gear up-dorsum in Morocco in 1905 that the fearfulness of encirclement began to be a potent cistron in German language politics."[23] [24] Few outside observers agreed with the notion of Frg as a victim of deliberate encirclement.[25] [26] English historian G. M. Trevelyan expressed the British viewpoint:

The encirclement, such as it was, was of Germany's own making. She had encircled herself by alienating France over Alsace-Lorraine, Russia by her support of Austro-hungarian empire's anti--Slav policy in the Balkans, England by building her rival fleet. She had created with Austro-hungarian empire a military bloc in the heart of Europe and then powerful and yet then restless that her neighbors on each side had no choice but either to go her vassals or to stand together for protection....They used their central position to create fear in all sides, in order to gain their diplomatic ends. And then they complained that on all sides they had been encircled.[27]

Bethmann-Hollweg was mesmerized by the steady growth of Russian power, which was in big part due to French financial and technical assistance. For the Germans, this deepened the worry ofttimes expressed by the Kaiser that Germany was being surrounded by enemies who were growing in strength.[28] I implication was that time was confronting them, and a war happening sooner would be more advantageous for Federal republic of germany than a state of war happening later. For the French, there was a growing fear that Russia would get significantly more powerful than France, and become more independent of France, possibly even returning to its old military machine alliance with Germany. The implication was that a state of war sooner could count on the Russian alliance, just the longer information technology waited the greater the likelihood of a Russian alliance with Germany that would doom French republic.[29]

French republic, a tertiary smaller than Germany, needed Russia's vast potential, and the fearfulness was that together the two would in a few years conspicuously surpass Federal republic of germany's military machine capability. This argued for war sooner rather than after. Bethmann-Hollweg knew he was undertaking a calculated risk by backing a local war in which Austria would politically destroy Serbia. The promise was to "localize" that war by keeping the other powers out of it. Russian federation had no treaty obligations to Serbia, but was trying to manner itself as the leader of the Slavic peoples in opposition to their German and Austrian oppressors. If Russia intervened to defend Serbia, Germany would have to arbitrate to defend Republic of austria, and very probable France would honor its treaty obligation and join with Russian federation. Bethmann-Hollweg assumed Britain had no interest in the Balkans and would remain neutral. It was also possible that Russia would go to war merely French republic would non follow, in which case the Triple Entente would get meaningless. The calculated risk failed when Russia mobilized. The German general staff, which was ever hawkish and eager for state of war, now took control of German language policy. Its war plan called for firsthand activity before Russia could mobilize much force, and instead use very rapid mobilization of German active duty and reserve forces to invade France through Kingdom of belgium. Once France was knocked out, the German language troops would be sent to the East to defeat Russia with the aid of the Austrian army. Once Russian federation mobilized, on July 31, Austria and Germany mobilized. The Germans had a very sophisticated program for rapid mobilization. It worked well while everyone else was days or weeks behind. The general staff convinced the Kaiser to activate their war plan, and Bethmann-Hollweg could only follow forth. Most historians care for the Kaiser as a man far out of his depth who was nether the spell of the Regular army Full general staff.[30]

In 1913, the Army Act raised Frg's peace strength to 870,000 men, and raising the eventual state of war strength from iv.5 million to five.4 million. France responded past expanding the preparation period for all draftees from two years to three. Russia too raised its army size to a wartime basis of 5.iv one thousand thousand. Austria in 1913 raised its war force to two.0 million. All the rival armies improved their efficiency, especially with more powerful arms and automobile guns.[31] [32]

The main war plan, the Schlieffen Plan, was drawn up by the Ground forces headquarters. It called for a great infantry sweep through Belgium to encircle Paris and defeat France in a matter of weeks. Then the forces would be moved by track to the Eastern Front, to defeat the Russians. The plan was not shared with the Navy, the Foreign Function, the Chancellor, the main marry in Vienna, or the separate Army commands in Bavaria and the other states. No 1 could indicate out bug or plan to coordinate with it. The generals who did know about it counted on it giving a quick victory within weeks—if that did not happen at that place was no "Plan B."[33] [34] No German language leaders had a long-term programme when the war began. There were no long-term goals—the commencement ones—the proposed "Septemberprogramm" was hurriedly put together in September 1914 afterward the war began and was never formally adopted.[35]

Rivalry with Britain [edit]

In explaining why neutral Britain went to war with Germany, Paul Kennedy (1980) recognized it was critical for state of war that Germany become economically more than powerful than U.k., but he downplays the disputes over economical merchandise imperialism, the Baghdad Railway, confrontations in Central and Eastern Europe, highly-charged political rhetoric and domestic pressure groups. Germany's reliance fourth dimension and once again on sheer power, while United kingdom increasingly appealed to moral sensibilities, played a role, specially in seeing the invasion of Belgium as a profound moral and diplomatic crime. Kennedy argues that by far the main reason was London's fright that a repeat of 1870 — when Prussia and the German language states smashed French republic in the Franco-Prussian State of war — would hateful that Germany, with a powerful army and navy, would control the English Channel and northwest France. British policymakers insisted that that would be a catastrophe for British security.[36]

[edit]

The British Royal Navy dominated the earth in the 19th century, simply after 1890, Germany attempted to challenge Britain'southward supremacy. The resulting naval race heightened tensions between the two nations. In 1897, Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz became German Naval Secretarial assistant of State and began transformation of the Majestic German Navy from a pocket-size, coastal defence force to a armada that was meant to challenge British naval power. Every bit part of the wider bid to modify the international balance of power decisively in Germany'southward favour, Tirpitz called for a Risikoflotte (Risk Fleet), so called because, although however smaller than the British fleet, it would be besides big for Uk to risk taking information technology on.[37] [38]

The German Navy, under Tirpitz, had ambitions to rival the Purple Navy and dramatically expanded its fleet in the early 20th century to protect the colonies, German commerce, the homeland, and to exert ability worldwide.[39] In 1890, to protect its new fleet, Germany traded possessions. It obtained the strategic island of Heligoland off the German N Sea coast and gave upwardly the island of Zanzibar in Africa.[40] In 1898, Tirpitz started a program of warship construction. The British, nonetheless, were always well alee in the race. The British Dreadnought battleship of 1907 was so advanced in terms of speed and firepower that all other warships were immediately made obsolete. Federal republic of germany copied it but never surged alee in quality or numbers.[41]

Blank cheque [edit]

Berlin repeatedly and urgently chosen on Vienna to human activity quickly in response to the assassination at Sarajevo on June 28, 1914, and then that a counter alliance would non have time to organize, and Austria could blame its intense acrimony at the atrocious act. Vienna delayed its disquisitional ultimatum until July 23, and its actual invasion until August xiii. That allowed time for the Russian-French opposition to organize. Information technology also allowed an investigation to turn upwards many details only no evidence pointing directly to the government of Serbia. The main reason for the delay was the fact that practically the entire Austrian regular army was tied down at habitation in harvest work, providing a food supply that would be essential for whatsoever war in one case the reserves were called to duty.[42] [43]

In July, 1914, Deutschland gave Austria a "blank bank check" in treatment its punishment of Serbia regarding the assassination of the heir to the Austrian throne. It meant that Frg would back up whatever conclusion Austria made. Austria decided on war with Serbia, which quickly led to escalation with Russia. Bethmann-Hollweg on July half dozen told the Austrian administrator in Berlin:

- Finally, as far as concerns Serbia, His Majesty, of course, cannot interfere in the dispute now going on between Austro-hungarian empire and that country, as it is a matter non inside his competence. The Emperor Francis Joseph may, nonetheless, rest assured that His Majesty will faithfully stand up past Austro-hungarian empire,[editor: Bethmann-Hollweg here deleted the phrase "nether all circumstances" which had appeared in his first draft] as is required past the obligations of his alliance and of his ancient friendship.[44]

Shortly after the war began, the High german foreign office issued a argument justifying the Blank Check as necessary for the preservation of Austria, and the Teutonic (German) race in central Europe. The statement said:

- it was clear to Republic of austria that information technology was non compatible with the nobility and the spirit of cocky-preservation of the monarchy to view idly any longer this agitation beyond the border. The Imperial and Imperial Government appraised Germany of this conception and asked for our opinion. With all our eye we were able to agree with our ally'southward estimate of the state of affairs, and assure him that any action considered necessary to finish the move in Servia [sic] directed against the conservation of the monarchy would meet with our blessing. We were perfectly aware that a possible warlike attitude of Austria-Republic of hungary against Servia might bring Russia upon the field, and that it might therefore involve u.s.a. in a war, in accordance with our duty as allies. We could non, however, in these vital interests of Austro-hungarian empire, which were at stake, propose our ally to have a yielding attitude not compatible with his dignity, nor deny him our assistance in these trying days. We could practice this all the less as our own interests were menaced through the continued Serb agitation. If the Serbs connected with the assist of Russian federation and France to menace the existence of Republic of austria-Republic of hungary, the gradual collapse of Austria and the subjection of all the Slavs under 1 Russian sceptre would exist the consequence, thus making untenable the position of the Teutonic race in Key Europe.[45]

July: crunch and war [edit]

In early on July 1914, in the aftermath of the assassination of Franz Ferdinand and the firsthand likelihood of war between Austria-Hungary and Serbia, the German authorities informed the Austro-Hungarian government that Frg would uphold its brotherhood with Austria-Hungary and defend information technology from possible Russian intervention if a state of war between Austria-hungary and Serbia took place.

Austria depended entirely on Germany for support – it had no other ally it could trust– just the Kaiser lost control of the German regime. Bethmann-Hollweg had repeatedly rejected pleas from United kingdom and Russia to put pressure on Republic of austria to compromise. German elite and popular public opinion also was demanding arbitration. Now in late July he reversed himself, and pleaded, or demanded, that Republic of austria accept mediation, warning that U.k. would probably bring together Russia and France if a larger war started. The Kaiser made a direct appeal to Emperor Franz Joseph forth the same lines. However, Bethmann-Hollweg and the Kaiser did non know that the German armed services had its own line of communication to the Austrian military, and insisted on rapid mobilization confronting Russia. German Chief of Staff Moltke sent an emotional telegram to the Austrian Chief of Staff Conrad on July 30: "Austria-Hungary must be preserved, mobilise at once confronting Russia. Germany will mobilise." Vienna officials decided that Moltke was really in charge—which was truthful—and refused mediation and mobilized against Russia.[46]

When Russia enacted a general mobilization, Germany viewed the human action equally provocative. The Russian government promised Germany that its general mobilization did not mean training for war with Germany but was a reaction to the events between Austro-hungarian empire and Serbia. The German government regarded the Russian promise of no state of war with Frg to be nonsense in light of its general mobilization, and Germany, in turn, mobilized for state of war. On ane Baronial, Deutschland sent an ultimatum to Russia stating that since both Germany and Russia were in a state of military mobilization, an constructive land of state of war existed between the two countries. Later that twenty-four hour period, France, an marry of Russia, declared a state of general mobilization. The German government justified military action confronting Russia as necessary because of Russian aggression as demonstrated by the mobilization of the Russian army that had resulted in Federal republic of germany mobilizing in response.[47]

After Frg declared war on Russian federation, France with its brotherhood with Russia prepared a general mobilization in expectation of war. On 3 August 1914, Germany responded to this activity by declaring war on French republic. Germany, facing a two-forepart war, enacted what was known every bit the Schlieffen Programme, which involved German armed forces needing to move through Belgium and swing south into France and towards the French majuscule of Paris. This programme aimed to gain a quick victory against the French and let High german forces to concentrate on the Eastern Front. Belgium was a neutral state and would non accept German forces crossing its territory. Frg disregarded Belgian neutrality and invaded the state to launch an offensive towards Paris. This acquired Bully United kingdom to declare state of war against the German Empire, as the activity violated the Treaty of London that both Britain and Prussia had signed in 1839 guaranteeing Belgian neutrality and defense of the kingdom if a nation reneged.

Subsequently, several states declared war on Germany in late Baronial 1914, with Italy declaring war on Austria-Hungary in 1915 and Deutschland on 27 August 1916; the United States on 6 April 1917 and Hellenic republic in July 1917.

Frg attempted to justify its actions through the publication of selected diplomatic correspondence in the German White Book[48] which appeared on iv Baronial 1914, the same day as U.k.'southward state of war proclamation.[49] In information technology, they sought to establish justification for their own entry into the war, and cast blame on other actors for the outbreak.[fifty] The White Book was but the starting time of such compilations to occur, including the British Blueish Volume two days later on, followed by numerous color books by the other European powers.[50]

Ottoman ally [edit]

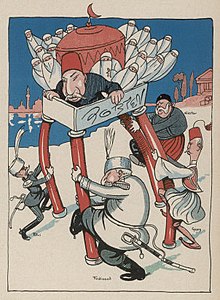

1912 Danish cartoon shows Balkan states tearing apart the rickety Ottoman Empire in the Beginning Balkan State of war, Oct 1912

Turkey had been desperately defeated in a series of wars in the previous decade, losing the 2 Balkan Wars of 1912–13 and the Italo-Turkish War in 1911–12.[51] However, relations with Germany had been fantabulous, involving investment aid in financing, and assistance for the Turkish army.[52] In late 1913 German general Liman von Sanders was hired to reorganize the army, and to command the Ottoman forces at Constantinople. Russia and French republic vigorously objected, and forced a reduction in his office. Russia had the long-term goal of sponsoring the new Slavic states in the Balkan region, and had designs on control of the Straits (assuasive entry into the Mediterranean), and even taking over Constantinople.[53]

There was a long-standing disharmonize between Britain and Frg over the Baghdad Railway through the Ottoman Empire. It would accept projected German ability toward Britain'south sphere of influence (India and southern Persia), was resolved in June 1914. Berlin agreed non to construct the line south of Baghdad, and to recognize U.k.'s preponderant interest in the region. The outcome was resolved to the satisfaction of both sides and did not play a role in causing the war.[54]

In June, 1914, Vienna and Berlin discussed bringing Bulgaria and Turkey into their war machine alliance, to neutralize the threat of the Balkan League nether Russian and French auspices. When the war broke out, the Ottoman Empire was officially neutral at showtime, but leaning toward the Central Powers. Promises of war loans, armed services coordination, and recovery of lost territories appealed to Turkish nationalists, especially the Immature Turks under Enver Pasha and the nationalist Commission of Union and Progress (Cup).[55] [56] [57]

The last conclusion [edit]

Canadian historian Holger Herwig summarizes the scholarly consensus on Germany'southward last decicion:

Berlin did not go to state of war in 1914 in a bid for 'world ability', equally historian Fritz Fischer claimed, only rather kickoff to secure and thereafter to enhance the borders of 1871. Secondly, the decision for war was fabricated in July 1914 and not, as some scholars have claimed, at a nebulous 'war council' on 8 December 1912. Thirdly, no one in Berlin had planned for war before 1914; no long-term economic or military machine plans accept been uncovered to suggest otherwise....The fact remains that on 5 July 1914 Berlin gave Vienna unconditional back up ('blank cheque') for a war in the Balkans....Noncombatant as well as military machine planners in Berlin, like their counterparts in Vienna, were dominated by a 'strike-now-better-than-later' mentality. They were enlightened that Russia's 'Big Programme' of rearmament...would be completely around 1916–17....No one doubted that war was in the offing. The diplomatic and political record...contains countless dire prognostications of the inevitability of a 'terminal reckoning' betwixt Slavs and Teutons. Leaders in Berlin also saw war equally the only solution to 'encirclement'....In short, war was viewed as both apocalyptic fearfulness and apocalyptic hope.[58]

See also [edit]

- History of Germany during Earth State of war I

- Anglo-German naval artillery race

- Causes of Globe War I

- Historiography of the causes of Globe War I

- Austro-Hungarian entry into World War I

- British entry into World War I

- French entry into World War I

- Italian entry into World War I

- Ottoman entry into Globe War I

- Russian entry into World War I

- Diplomatic history of World War I

- History of German language foreign policy

- International relations of the Great Powers (1814–1919)

- Key Powers

- Allies of World War I

- Home front during World State of war I roofing all major countries

Notes [edit]

- ^ Mark Hewitson. Federal republic of germany and the Causes of the First Earth War (2004) pp. 1–20.

- ^ Christopher Clark, The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to State of war in 1914 (2012)

- ^ F. H. Hinsley, ed. The New Cambridge Modern History, Vol. 11: Material Progress and Globe-Wide Problems, 1870–98 (1962) pp 204–42, esp 214–17.

- ^ Paul Chiliad. Kennedy, ed., The War Plans of the Cracking Powers, 1880–1914 (1979)

- ^ Hinsley (1962) pp 204–42.

- ^ Craig, "The World War I Alliance of the Key Powers in Retrospect: The War machine Cohesion of the Alliance"

- ^ Richard W. Kapp, "Bethmann-Hollweg, Republic of austria-Republic of hungary and Mitteleuropa, 1914–1915." Austrian History Yearbook xix.1 (1983): 215-236.

- ^ Richard W. Kapp, "Divided Loyalties: The German language Reich and Austria-Hungary in Austro-German Discussions of State of war Aims, 1914–1916." Primal European History 17.2-three (1984): 120-139.

- ^ T,Yard, Otte, July Crisis (2014) pp. xvii–xxii for a list.

- ^ Konrad H. Jarausch, "The Illusion of Limited War: Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg's Calculated Risk, July 1914" Primal European History 2.1 (1969): 48–76. online

- ^ Lamar Cecil, Wilhelm 2: Emperor and Exile, 1900–1941 (1996).

- ^ Craig, Gordon A. The politics of the Prussian army 1640–1945 (1955) pp 292–95.

- ^ Geoff Eley, "Reshaping the right: Radical nationalism and the German language Navy League, 1898–1908." Historical Journal 21.ii (1978): 327–40 online.

- ^ Marilyn Shevin Coetzee, The High german Army League: Pop Nationalism in Wilhelmine Germany (1990)

- ^ Roger Chickering, . We men who experience most German language: a cultural study of the Pan-German League, 1886–1914 (1984).

- ^ Dieter Groh, "The 'Unpatriotic Socialists' and the State." Journal of Contemporary History 1.4 (1966): 151–177. online.

- ^ V. R. Berghahn, Deutschland and the Arroyo of State of war in 1914 (1974) pp 178–85

- ^ Margaret MacMillan, The state of war that ended peace p. 605.

- ^ Jeffrey Verhey, The Spirit of 1914: Militarism, Myth, and Mobilization in Deutschland (2000) pp 17–20.

- ^ Paul W. Schroeder, "Earth War I equally Galloping Gertie: A Reply to Joachim Remak," Journal of Modern History 44#three (1972), pp. 319–45, at p/ 320 online

- ^ Schroeder p 320

- ^ Matthew S. Seligmann, "'A Barometer of National Confidence': a British Assessment of the Role of Insecurity in the Formulation of German Military machine Policy before the Commencement World War." English Historical Review 117.471 (2002): 333–55. online

- ^ Gordon A. Craig, Germany 1866-1945 (1978) p. 321

- ^ E. Malcolm Carroll, Germany and the peachy powers, 1866–1914: A study in public opinion and foreign policy (1938) pp 485ff, 830.online

- ^ Imanuel Geise, German strange policy 1871-1914 (1976) pp 121-138.

- ^ Hermann Kantorowicz, The spirit of British policy and the myth of the encirclement of Federal republic of germany (London: G. Allen & Unwin, 1931).

- ^ George Macaulay Trevelyan, British history in the 19th century and subsequently 1782-1919 (1937) p 463.

- ^ Jo Groebel and Robert A. Hinde, ed. (1989). Aggression and War: Their Biological and Social Bases. p. 196.

- ^ Otte, July Crisis (2014) pp 99, 135–36.

- ^ Konrad H. Jarausch, "The Illusion of Express War: Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg's Calculated Risk, July 1914", Key European History two.ane (1969): 48–76. online

- ^ Frank Maloy Anderson; Amos Shartle Hershey (1918). Handbook for the Diplomatic History of Europe, Asia, and Africa, 1870–1914. U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 471–72.

- ^ Members of the Oxford Faculty (1914). Why Nosotros are at War, Great Britain'southward Example. p. 45.

- ^ Holger H. Herwig, "Through the Looking Glass: German Strategic Planning before 1914" The Historian 77#2 (2015) pp 290–314.

- ^ Peter Padfield, The Great Naval Race: The Anglo-German Naval Rivalry, 1900–1914 (2005) p 335.

- ^ Wayne C. Thompson, "The September Program: Reflections on the Bear witness." Central European History xi.4 (1978): 348-354. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008938900018823

- ^ Paul Yard. Kennedy, The Ascent of the Anglo-German Antagonism, 1860–1914 (1980) pp 464–lxx.

- ^ William 50. Langer, The affairs of imperialism: 1890–1902 (1951) pp 433–42.

- ^ Peter Padfield, The Keen Naval Race: Anglo-High german Naval Rivalry 1900–1914 (2005)

- ^ David Woodward, "Admiral Tirpitz, Secretary of Land for the Navy, 1897–1916," History Today (July 1963) xiii#8 pp. 548–55.

- ^ David R. Gillard, "Salisbury'southward African Policy and the Heligoland Offer of 1890." English language Historical Review 75.297 (1960): 631–53. online

- ^ Holger H. Herwig, "The German reaction to the Dreadnought revolution." International History Review 13.2 (1991): 273–83.

- ^ Richard F. Hamilton, and Holger H. Herwig, Decisions for War, 1914–1917 (2004) pp. 63–67.

- ^ Samuel R. Williamson, Jr. "Confrontation With Serbia: The Consequences of Vienna's Failure to Accomplish Surprise in July 1914" Mitteilungen des Österreichischen Staatsarchivs 1993, Vol. 44, pp 168–77.

- ^ Claudia Durst Johnson; James H. Meredith (2004). Agreement the Literature of World War I: A Student Casebook to Issues, Sources, and Historical Documents. Greenwood. pp. 13–14.

- ^ See "The German White Book" (1914)

- ^ Margaret MacMillan, The State of war That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 (2013) pp 605–07.

- ^ Richard F. Hamilton and Holger H. Herwig, Decisions for State of war, 1914–1917 (2004), pp lxx–91.

- ^ von Mach, Edmund (1916). Official Diplomatic Documents Relating to the Outbreak of the European State of war: With Photographic Reproductions of Official Editions of the Documents (Blue, White, Yellow, Etc., Books). New York: Macmillan. p. vii. LCCN 16019222. OCLC 651023684.

- ^ Schmitt, Bernadotte E. (one April 1937). "France and the Outbreak of the World War". Foreign Affairs. Council on Strange Relations. 26 (3): 516. doi:10.2307/20028790. JSTOR 20028790. Archived from the original on 25 November 2018.

- ^ a b Hartwig, Matthias (2014). "Color books". In Bernhardt, Rudolf; Bindschedler, Rudolf; Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Police force and International Law (eds.). Encyclopedia of Public International Law. Vol. 9 International Relations and Legal Cooperation in General Diplomacy and Consular Relations. Amsterdam: North-Holland. p. 24. ISBN978-1-4832-5699-iii. OCLC 769268852.

- ^ R. Ernest Dupuy and Trevor N. Dupuy, The Encyclopedia of Armed forces History from 3500 B.C. to the Present (1977) pp 926–28.

- ^ Frank G. Weber, Eagles on the crescent: Deutschland, Austria, and the affairs of the Turkish alliance, 1914–1918 (1970).

- ^ Alastair Kocho-Williams (2013). Russia's International Relations in the Twentieth Century. Routledge. pp. 12–19.

- ^ Mustafa Aksakal (2008). The Ottoman Road to War in 1914: The Ottoman Empire and the Commencement World State of war. pp. 111–13.

- ^ F. W. Beckett, "Turkey'southward Momentous Moment." History Today (June 2013) 83#6 pp 47–53.

- ^ Hasan Kayalı, "The Ottoman Experience of World State of war I: Historiographical Problems and Trends," Periodical of Modern History (2017) 89#iv: 875–907. https://doi.org/10.1086/694391.

- ^ Mustafa Aksakal (2008). The Ottoman Road to War in 1914: The Ottoman Empire and the First World State of war.

- ^ Holger H. Herwig, The First World War: Germany and Austria-Republic of hungary 1914–1918 (1997) p. 19.

Further reading [edit]

- Afflerbach, Holger. "Wilhelm II as Supreme Warlord in the Starting time World War." War in History five.four (1998): 427–49.

- Albertini, Luigi. The Origins of the State of war of 1914 (3 vol 1952). vol two online covers July 1914

- Albrecht-Carrié, René. A Diplomatic History of Europe Since the Congress of Vienna (1958), 736pp; basic survey.

- Balfour, Michael. The Kaiser and his Times (1972) online

- Berghahn, V. R. Federal republic of germany and the Approach of State of war in 1914 (1973), 260pp; scholarly survey, 1900 to 1914

- Brandenburg, Erich. (1927) From Bismarck to the Globe State of war: A History of German Foreign Policy 1870–1914 (1927) online.

- Buse, Dieter G., and Juergen C. Doerr, eds. Modernistic Deutschland: an encyclopedia of history, people and culture, 1871–1990 (ii vol. Garland, 1998.

- Butler, Daniel Allen. Burden of Guilt: How Germany Shattered the Last Days of Peace (2010) extract, popular overview.

- Carroll, E. Malcolm. Deutschland and the corking powers, 1866–1914: A written report in public opinion and foreign policy (1938) online; 862pp; written for advanced students.

- Cecil, Lamar Wilhelm II: Emperor and Exile, 1900–1941 (1996), a scholarly biography

- Clark, Christopher. The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914 (2013) extract

- Sleepwalkers lecture by Clark. online

- Coetzee, Marilyn Shevin. The German language Army League: Popular Nationalism in Wilhelmine Deutschland (1990)

- Craig, Gordon A. "The World War I brotherhood of the Central Powers in retrospect: The military cohesion of the brotherhood." Periodical of Modernistic History 37.3 (1965): 336–44. online

- Craig, Gordon. The Politics of the Prussian Army: 1640–1945 (1964).

- Craig, Gordon. Germany, 1866–1945 (1978) online free to infringe

- Evans, R. J. W.; von Strandmann, Hartmut Pogge, eds. (1988). The Coming of the First Globe War. Clarendon Press. ISBN978-0-19-150059-6. essays by scholars from both sides

- Fay, Sidney B. The Origins of the Globe State of war (2 vols in one. 2nd ed. 1930). online, passim

- Fischer, Fritz. "1914: Germany Opts for War, 'Now or Never'", in Holger H. Herwig, ed., The Outbreak of World State of war I (1997), pp. 70–89.

- Fromkin, David. Europe's Last Summer: Who Started the Swell State of war in 1914? (2004).

- Geiss, Imanuel. "The Outbreak of the Kickoff World War and High german State of war Aims," Journal of Contemporary History ane#3 (1966), pp. 75–91 online

- Gooch, G.P. Franco-German Relations 1871–1914 (1923). 72pp

- Unhurt, Oron James. Publicity and Affairs: With Special Reference to England and Germany, 1890–1914 (1940)

- Hamilton, Richard F. and Holger H. Herwig, eds. Decisions for War, 1914–1917 (2004), pp 70–91, a scholarly summary.

- Hensel, Paul R. "The Development of the Franco-German Rivalry" in William R. Thompson, ed. Great power rivalries (1999) pp 86–124 online

- Herwig, Holger H. "Germany" in Richard F. Hamilton, and Holger H. Herwig, eds. The Origins of Earth War I (2003), pp 150–87.

- Herwig, Holger H. The First World War: Deutschland and Austria-Republic of hungary 1914–1918 (1997) pp vi–74.

- Herweg, Holger H., and Neil Heyman. Biographical Dictionary of World War I (1982).

- Hewitson, Mark. "Germany and France before the First World State of war: a reassessment of Wilhelmine foreign policy." English language Historical Review 115.462 (2000): 570-606; argues Deutschland had a growing sense of war machine superiority

- Hewitson, Mark. Germany and the Causes of the Showtime World State of war (2004), thorough overview

- Jarausch, Konrad (1973). Von Bethmann-Hollweg and the Hubris of Imperial Germany. Yale Academy Printing.

- Jarausch, Konrad H. "The Illusion of Limited War: Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg's Calculated Risk, July 1914." Central European History two.1 (1969): 48–76. online

- Jarausch, Konrad Hugo. "Revising German History: Bethmann-Hollweg Revisited." Central European History 21#3 (1988): 224–43, historiography in JSTOR

- Joll, James; Martel, Gordon (2013). The Origins of the First World State of war (3rd ed.). Taylor & Francis.

- Kapp, Richard Westward. "Divided Loyalties: The High german Reich and Austria-Hungary in Austro-German Discussions of War Aims, 1914–1916." Cardinal European History 17.ii-3 (1984): 120-139.

- Kennedy, Paul. The Rise of the Anglo-German language Antagonism 1860–1914 (1980) pp 441–70.extract and text search

- Kennedy, Paul. The Rising and Fall of the Neat Powers (1987), pp 194–260. online free to borrow

- Kennedy, Paul. The Rise and Autumn of British Naval mastery (1976) pp 205–38.

- Kennedy, Paul Thou. "Idealists and realists: British views of Deutschland, 1864–1939." Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 25 (1975): 137–56. online

- McMeekin, Sean. July 1914: Inaugural to War (2014) scholarly account, day-by-solar day

- MacMillan, Margaret (2013). The State of war That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914. Random Business firm. ; major scholarly overview

- Massie, Robert M. Dreadnought: Britain, Germany, and the coming of the Nifty State of war (Random House, 1991) extract see Dreadnought (book), pop history

- Mayer, Arno. "The Primacy of Domestic Politics", in Holger H. Herwig, ed., The Outbreak of World War I (1997), pp. 42–47.

- Mombauer, Annika. "German War Plans" in Richard F. Hamilton and Holger H. Herwig, eds. State of war Planning 1914 (2014) pp 48–79

- Mombauer, Annika and Wilhelm Deist, eds. The Kaiser: New Research on Wilhelm II'southward Role in Majestic Federal republic of germany (2003)

- Murray, Michelle. "Identity, insecurity, and keen power politics: the tragedy of German naval ambition before the Start Globe War." Security Studies 19.4 (2010): 656–88. online

- Neiberg, Michael Southward. Dance of the Furies: Europe and the Outbreak of World War I (2011), on public stance

- Otte, T. G. July Crisis: The World's Descent into War, Summer 1914 (Cambridge Upward, 2014). online review

- Paddock, Troy R. East. A Call to Arms: Propaganda, Public Opinion, and Newspapers in the Swell War (2004)

- Padfield, Peter. The Bully Naval Race: Anglo-German Naval Rivalry 1900–1914 (2005)

- Papayoanou, Paul A. "Interdependence, institutions, and the balance of ability: Britain, Germany, and World War I." International Security xx.4 (1996): 42-76.

- Pratt, Edwin A. The ascent of rail-power in state of war and conquest, 1833–1914 (1915) online

- Rich, Norman. "The Question Of National Interest In Imperial German Foreign Policy: Bismarck, William II, and the Road to World War I." Naval War College Review (1973) 26#i: 28-41. online

- Rich, Norman. Great Power Diplomacy: 1814–1914 (1991), comprehensive survey

- Ritter, Gerhard. The Sword and the Sceptre, Vol. ii – The European Powers and the Wilhelmenian Empire 1890–1914 (1970) Covers military policy in Deutschland and too France, Britain, Russia and Austria.

- Scheck, Raffael. "Lecture Notes, Federal republic of germany and Europe, 1871–1945" (2008) full text online, a brief textbook by a leading scholar

- Schmitt, Bernadotte Due east. "Triple Alliance and Triple Entente, 1902–1914." American Historical Review 29.3 (1924): 449–73. in JSTOR

- Schmitt, Bernadotte Everly. England and Germany, 1740–1914 (1916). online

- Scott, Jonathan French. 5 Weeks: The Surge of Public Opinion on the Eve of the Slap-up War (1927) pp 99–153

- Seligmann, Matthew S. "'A Barometer of National Conviction': A British Assessment of the Role of Insecurity in the Formulation of German Military Policy before the Commencement World War." English Historical Review 117#471, (2002), pp. 333–55, online

- Stowell, Ellery Cory. The Diplomacy of the State of war of 1914 (1915) 728 pages online free

- Strachan, Hew Francis Anthony (2004). The First Earth War. Viking. ISBN978-0-670-03295-2.

- Stuart, Graham H. French strange policy from Fashoda to Serajevo (1898–1914) (1921) 365 pp online

- Taylor, A.J.P. The Struggle for Mastery in Europe 1848–1918 (1954) online free

- Tucker, Spencer C., ed. The European Powers in the First Globe War: An Encyclopedia (1996) 816pp.

- Verhey, Jeffrey. The Spirit of 1914: Militarism, Myth, and Mobilization in Frg (2006) extract

- Vyvyan, J. G. K. "The Arroyo of the War of 1914." in C. L. Mowat, ed. The New Cambridge Modern History: Vol. XII: The Shifting Residue of Earth Forces 1898–1945 (2nd ed. 1968) online pp 140–seventy.

- Watson, Alexander. Ring of Steel: Germany and Austria-Hungary in Globe War I (2014) pp 7–52. excerpt

- Wertheimer, Mildred. The Pan-German language League, 1890–1914 (1924) online

- Williamson Jr., Samuel R. "High german Perceptions of the Triple Entente later 1911: Their Mounting Apprehensions Reconsidered" Foreign Policy Analysis 7.2 (2011): 205–fourteen.

- Woodward, East.L. Great Britain And The German Navy (1935) 535pp; scholarly history online

- "British Entry into World War I: Did the Germans Have Reason to Incertitude that the British Would Declare State of war in 1914?" in Paul du Quenoy ed., History in Dispute Vol. 16: Twentieth-Century European Social and Political Movements: First Series (St. James Printing 2000; Gale E-Books) 10pp summary of debate

Historiography [edit]

- Cornelissen, Christoph, and Arndt Weinrich, eds. Writing the Not bad State of war – The Historiography of World War I from 1918 to the Present (2020) complimentary download; full coverage for major countries.

- Evans, R. J. W. "The Greatest Ending the World Has Seen" The New York Review of Books Feb 6, 2014 online

- Ferguson, Niall. "Frg and the origins of the Offset World War: new perspectives." Historical Journal 35.iii (1992): 725–52. online free

- Herwig, Holger H. ed., The Outbreak of World War I: Causes and Responsibilities (1990) excerpts from master and secondary sources

- Hewitson, Marking. "Federal republic of germany and France before the Offset World State of war: a reassessment of Wilhelmine strange policy." English Historical Review 115.462 (2000): 570-606; argues Germany had a growing sense of military superiority. online

- Hewitson, Mark. Federal republic of germany and the Causes of the First World War (2004) pp i–20 on historians.

- Horne, John, ed. A Companion to World War I (2012), 38 topical essays past scholars

- Janssen, Karl-Heinz. "Gerhard Ritter: A Patriot Historian's Justification," in H. W. Koch, ed., The Origins of the First World War (1972) pp. 292-318.

- Joll, James. "The 1914 Contend Continues: Fritz Fischer and His Critics," in H. W. Koch, ed., The Origins of the Showtime World War (1972), pp. 13-29.

- Kramer, Alan. "Recent Historiography of the First World War – Part I", Periodical of Modern European History (Feb. 2014) 12#1 pp 5–27; "Recent Historiography of the First World War (Function Ii)", (May 2014) 12#2 pp 155–74.

- Langdon, John W. "Emerging from Fischer'south Shadow: contempo examinations of the crunch of July 1914." History Instructor 20.one (1986): 63–86, in JSTOR emphasis on roles of Germany and Austria.

- Mombauer, Annika. "Guilt or Responsibility? The Hundred-Year Argue on the Origins of World State of war I." Primal European History 48.4 (2015): 541–64.

- Mombauer, Annika. The origins of the Offset Earth War: controversies and consensus. (2002)

- Mommsen, Wolfgang J. "The Debate on German War Aims," Journal of Gimmicky History (1966) 1#3 pp 47–72. online; surveys Fischer argue

- Mulligan, William. "The Trial Continues: New Directions in the Report of the Origins of the Starting time Earth War." English Historical Review (2014) 129#538 pp: 639–66.

- Seligmann, Matthew Due south. "Frg and the origins of the First World War in the eyes of the American diplomatic establishment." German language History 15.three (1997): 307–32.

- Winter, Jay. and Antoine Prost eds. The Great War in History: Debates and Controversies, 1914 to the Present (2005)

Primary sources [edit]

- Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. Austro-Hungarian red book. (1915) English translations of official documents to justify the war. online

- Albertini, Luigi. The Origins of the War of 1914 (3 vol 1952).

- Barker. Ernest, et al. eds. Why we are at war; Slap-up United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland's instance (tertiary ed. 1914), the official British case confronting Frg. online

- Dugdale, Eastward.T.South. ed. German Diplomatic Documents 1871–1914 (four vol 1928–31), in English language translation. online

- Feldman, Gerald D. ed. German Imperialism, 1914–18: The Development of a Historical Debate (1972) 230 pp primary sources in English language translation.

- The German White Volume (1914) online official defense of Deutschland; see The German White Book

- another re-create

- Geiss, Imanuel, ed. July 1914, The outbreak of the Get-go World War: Selected Documents (1968).

- Geiss, Imanuel. German foreign policy 1871–1914 documents pp 192–218.

- Gooch, G.P. Recent revelations of European diplomacy (1928) pp 3–101. online

- U.s.. War Dept. General Staff. Strength and organization of the armies of French republic, Germany, Austria, Russia, England, Italia, Mexico and Japan (showing conditions in July, 1914) (1916) online

- Major 1914 documents from BYU

- "The German White Book" (1914) English translation of documents used by Frg to defend its actions

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_entry_into_World_War_I

0 Response to "to what extent was germany to blame for the outbreak of the first world war 1? tangled alliance"

Post a Comment